Toolshed Technologies

Andy Hunt

Musician, Author, Programmer

Thank you!

You are now subscribed to my low-volume newsletter, with my thoughts on modern software development, creativity, and skill growth.

To get started, here are my five steps to creativity. I hope you find these helpful!

/\ndy

Five Steps to Guaranteed Creativity

Take Advantage of How Your Brain Really Works

High-performing software development teams require innovation and highly creative solutions to problems. “Creativity” isn’t just something you can buy. However, it is something you can cultivate and practice. In fact, you can become a highly creative person (in any field, not just technology) by following these five steps:

- Gather the raw material

- Work it

- Forget the whole thing

- Eureka! (Or, “my that’s peculiar…”)

- Develop

Each of these steps takes advantage of how our brains really work — not how we’d like them to work.

Let’s take a look at each step and see what it means and how to do it well.

Step 1: Gather Raw Material

To start any creative endeavor, you must first gather the raw material for your project. This material could include raw facts from reading and researching, insights that occur to you, or open questions you may have. The idea is to gather them all together in a pile so that you can pick out the best ideas as you need them.

A good metaphor for this activity is building a stone wall out of rocks you find in the field.

You gather a bunch of stones in a pile, then when you need one just this size and shape, you pick through and find it (see Weinberg on Writing: The Fieldstone Method by Gerald Weinberg).

But ideas, facts, and insights can be harder to find than rocks lying in a field.

Here are some techniques that can help:

- Read deliberately with SQ3R

- Harvest insights

- Step away from the computer

- Use an exocortex

Let’s take a look at each of these raw material gathering techniques.

Read Deliberately with SQ3R

SQ3R is a book reading technique to help maximize understanding and retention. Instead of just reading a book linearly, from start to finish, you make several passes:

- Survey: scan the table of contents and any chapter summaries for an overview of the work.

- Question: note any questions you have that you want answered.

- Read: the work in its entirety. Make notes as you go.

- Recall: quiz yourself. Try and remember core facts, essential processes.

- Review: reread the work, expand and flesh out your notes, discuss the subject with other people.

Harvest Insights

Your brain contains various areas that function together in different ways. For instance, one particular activation network of different regions work together to allow you to focus and concentrate on a task. The default mode network (DMN) activates when you aren’t focused on any particular task. But just because you aren’t focused on one thing does not mean that your brain is idle. In fact, accessing the DMN is a rich source of fresh insight and ideas. Your brain already has these ideas, but they aren’t necessarily available to your conscious self. You can get easier access to these insights while in a hypnogogic or hypnopompic state. That is, just as you’re drifting off to sleep, or first thing when you wake up.

Thomas Edison often took advantage of this idea and would take a nap holding a cup of ball bearings. Just as he fell asleep, the bearings would clatter to the floor and wake him. He’d immediately write down whatever he was thinking about. If you don’t fancy picking up a few hundred ball bearings every day, there’s a better way.

A very popular technique taught everywhere from writing workshops to MBA courses is Morning Pages. First thing in the morning, before your feet even hit the floor, write out three pages of text. Whatever is on your mind. Stick to these ground rules:

- Write three pages, longhand (no typing)

- Uncensored, write it all out no matter if it seems stupid or irrelevant

- Do not skip a day

After a week or two, go back and review your pages for interesting thoughts and ideas.

Step AWAY from the Computer

Because of how your brain’s activation networks work with each other, you will tend to get flashes of insight just about anywhere — while washing the dishes, taking a shower, mowing the lawn, and so on. Everywhere except in front of the computer. The brain networks that process symbols interfere with your ability to generate insights. You may have experienced this when you’ve been stuck on a problem. You get up from your keyboard to take a walk, and a few minutes later the answer pops into your head.

Use an Exocortex

The most important step in harvesting insights is to keep track of them. When an idea, solution, or insight pops into your head the worst thing you can do is think, “I’ll remember that later.” You will not. Instead, you need to write it down or capture it somehow.

You can go old-school with a Fisher Space Pen and small notepad, or use a note-taking app on your phone, or call and leave yourself a voicemail that will be transcribed to text.

Not only will this help you gather your “fieldstones” of ideas, but it also takes advantage of another brain phenomenon. The more ideas you actively notice, the more ideas your brain will produce.

Notice good ideas to get more good ideas

Step 2: Work it

Now that you have the raw material, it’s time to deliberately work it for new ideas and insights. There are a few rules to follow while doing this:

- Don’t multitask. Work on this and only this. No social media or TV.

- Create boundaries in space and time. You need a distraction-free zone to work in.

- Play freely with the ideas in your pile.

You need to create a space that is separate from everyday life. Maybe it’s an attic office, or a park, or a coffee shop.

Give yourself an hour or two to just play with the ideas. Try not to be too goal-oriented, the work here is to see relationships, connect thoughts, and generate insights.

Play “Freely” means it’s okay to fail

Use Hand-Drawn Mindmaps

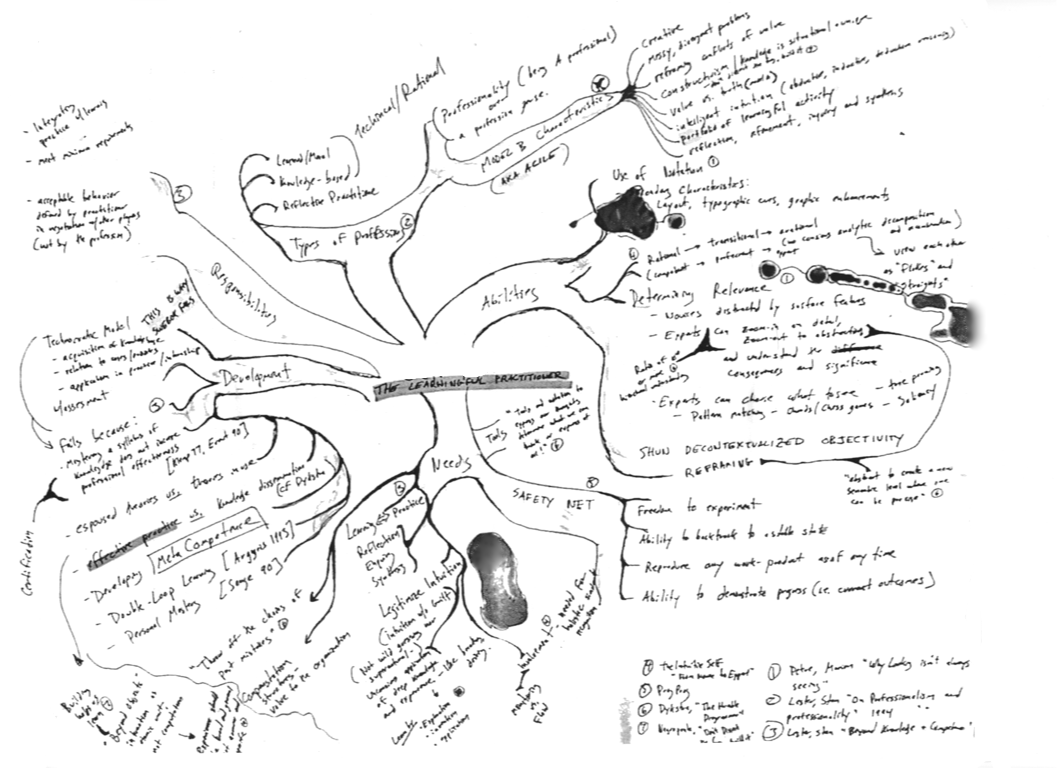

Many school children across the world are familiar with mindmaps, a simple graphical way of representing ideas and their relationships. (For some reason, mindmaps are much less common in the United States.) To make a mind map, take a piece of paper and draw a small circle in the middle of it with your central idea. As you get your facts, discoveries, and flashes of insight, add them to the mind map. Maybe they connect to other ideas already, maybe they don’t — that’s okay.

Here’s an example:

When studying your mind map, ask yourself these questions:

- How are these things related?

- What else do you see?

- What else do you know?

- What else do you imagine?

And add to your mind map as you go.

Now you might be tempted to use a computer-based mindmapping program. Don’t. Any computer-based approach has two significant problems. First, just using the computer itself tends to suppress your DMN, stifling creativity. Second, a computer program will inflict limitations on you. Many tend to force you into an outline mode, or implicit hierarchy. You don’t want that sort of accidental influence to affect your thought processes.

Drawing by hand doesn’t have those limitations. It’s more DMN friendly, and using both large and fine motor functions involves more of the brain. It’s non-hierarchical (unless you want it to be). There’s always room to squish in something extra. Different colors and textures increase brain activity. Even just deciding what colors or styles to use forces you to think of issues of taxonomy or ontology, and can help you illuminate new relationships and provide new insights.

A hand-drawn mindmap doesn’t have to be just words. Adding little pictures, icons, or whole scenes can help you express and analyze your thoughts.

Doodling is a powerful tool

Try Abnormal Thinking

Part of “working” the ideas is to think abnormally. That is, normal thinking is to be “right” at each stage. But that’s not what you want to do here. Instead, you want to play with deliberately crazy connections. Allow things that are (for now) impossible. Make purely random connections. What’s interesting about that? Anything? Ask yourself, “What would happen if…” Bend reality in impossible ways if you need to, but think about it.

Try coming at a problem from the opposite direction. For example, when you are trying to fix an elusive bug, you might deliberately try to cause it from multiple areas. Use that same principle here.

Once you’ve got an interesting mindmap written out, you’re ready for the next critical step: Forget about it.

Step 3: Forget the Whole Thing

Seriously. Stop thinking about it. Just stop.

You want to avoid thinking about the topic directly. Instead, hold the idea “lightly.” Don’t focus on something else, just don’t focus at all. Let your mind wander.

Again, this happens to programmers all the time — walk away from the keyboard. Take a stroll around your home or office. Walk the dog. Do the dishes. Do some fairly mindless task, as these non-directed activities tend to help your DMN access.

Step 4: Eureka!

When that flash of insight does come, tradition says you should proclaim, “eureka!” (ancient Greek for “I have found it”).

But it’s more likely that you won’t feel like it’s a “eureka” moment. Instead, you might experience something closer to “my, that’s peculiar,“ or “I wonder why…,“ or “isn’t there a way to…”

Be sure to have your notebook ready. At some random, asynchronous time, something important will occur to you. Be sure you have the means to capture it.

Don’t rush to “find a solution.” And you’ll want to rush right into it because uncertainty scares us. When we’re scared we can’t think creatively. Accordingly, even something as simple as a deadline can panic the mind into failure mode.

Srini Pillay, a Harvard psychologist, tells us, “The ambiguity inherent in uncertain choices activates the fear center of the brain, thereby disrupting the thinking processes critical to successful innovation.”

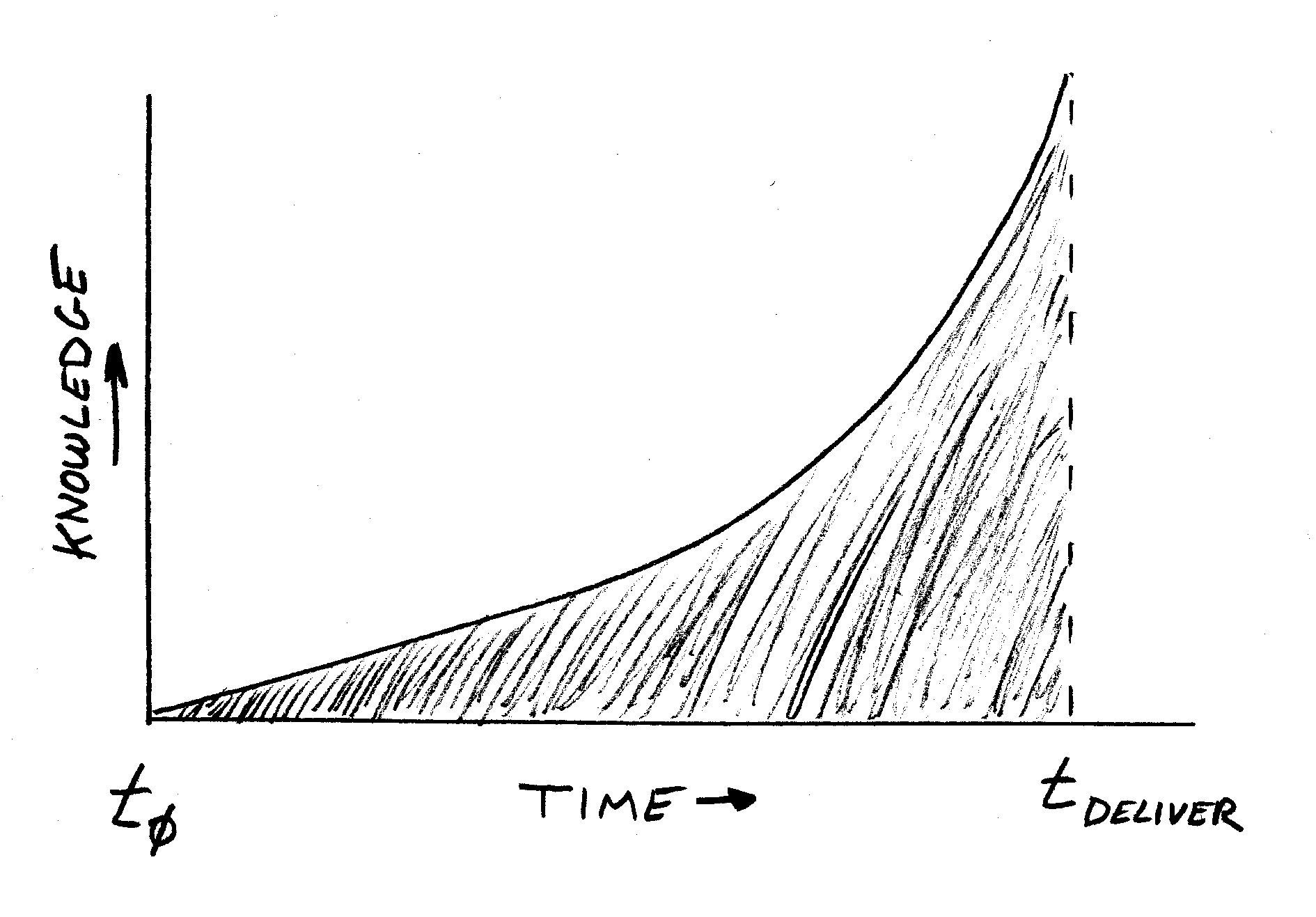

And if that’s not bad enough, our tendency to try and decide quickly, with confidence, strangles creativity. In the early stages of a project, you don’t know enough about the dynamics of the problem yet. That knowledge increases over time:

Tolerate the discomfort of the unsolved problem

Step 5: Develop

Once you’re comfortable that you have some interesting insights and are ready to develop your ideas, it’s time to try them out in the real world.

You’re not done with the mind map, of course. In fact, you want to leave the subject “open.”

Leave the mind map out on your desk or a table for easy, constant access. Pick at it. Constantly review and doodle on it as ideas strike you.

But as the abstract ideas on your mind map run aground against the hard edges of reality, you’ll need some additional mental tools.

Make a Wiki

Everyone is familiar with Wikipedia, perhaps the world’s largest example of user-editable, linkable web pages. You can make your own wiki of course, and many online service providers and desktop programs offer wiki pages as part of their product (like Github, Gitlab, MediaWiki, SharePoint, OneNote, and so on). A wiki is a great place to take more detailed notes than would be appropriate in a mindmap.

As you learn and discover more about your topic, you’ll want to create content. For example, every time I learn a new programming language, the first thing I do is make a cheat sheet. When learning or reading, I’m always making some combination of notes, summaries, highlights, cheat sheets, PostIt flags, recipes, code fragments, how-to’s, and so on. This habit can help you in a couple of different ways:

- The act of writing notes is more helpful to memory retention than repetition or other habits.

- By being deliberate about your ideas, you will be more attuned to spotting related ideas in the wild. This is related to the phenomenon known as sense tuning. For example, if I talk about the color red, suddenly you may notice red everywhere around you.

- By keeping track of good ideas, your brain will begin to produce more of them.

Now It’s Time to Try It

Start small, fail fast, learn fast, correct quickly. Rapid prototyping with feedback is the key. If you’re writing software, maybe mock up your idea in a language suited to rapid development (for example, Python or Ruby), even if your eventual implementation may have to be in something more performant and production-oriented (Elixir or Rust, perhaps). You might not even want to prototype in code at all — PostIt notes and whiteboards can be great tools for getting fast user feedback.

Although we often talk about testing code, you need to test your thoughts as well. Maybe this is a great, world-changing idea. Maybe it’s not. Critically analyze your own thought processes. For example, consider these loaded phrases. If you find yourself thinking the thought on the left, ask yourself the question on the right:

- “I know this will work”… How do you know?

- “Everyone is using xyz”… Says who?

- “I know it won’t work…” How specifically?

- “That’s better/cheaper than…” Compared to what or whom?

- “We can’t do that/have to do that” What would happen if you did (didn’t)?

Get Started

As with any new habit, the first steps are always the hardest. Find a slot in your schedule or daily routine when you can have 30–60 minutes of uninterrupted thinking time. Maybe you can fit that in only a few times a week. Try to at least look at the material for a few minutes every day to keep it fresh in your head, even if you can’t afford a full session.

Keep at for at least a month, and you’ll be well on your way to your own creative breakthrough. Good luck!

/\ndy

While you’re waiting for the next newsletter, here are some of the latest happenings on my site:

Latest News

-

Greenfield, Brownfield... Blackfield?

July 24, 2024 -

New article: The Limits of Process

January 25, 2022 -

New article: Habits vs. Practices

January 5, 2022 - List All News...